PRESS RELEASE ON THE CONTROVERSIAL CABLE CAR PROJECT FOR THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE OF MONEMVASIA, GREECE

THE ASSOCIATION OF THE FRIENDS OF MONEMVASIA

PRESS RELEASE ON THE CONTROVERSIAL CABLE CAR PROJECT FOR

THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE OF MONEMVASIA, GREECE:

MANY QUESTIONS AND ONLY FEW ANSWERS

In a nutshell: The site and the planned project

In a nutshell: The site and the planned project Monemvasia is a huge rock that was detached from the southeastern Peloponnese in southern Greece and juts out into the Aegean Sea. The rock was first inhabited by people who sought shelter from raids in the 6th century CE. People first settled and fortified the top of the rock and later a part of the foothills, in what are now – respectively – the ruined Upper Town and the inhabited Lower Town of the Castle of Monemvasia. Monemvasia developed into a strategic and commercial hub of communication between Byzantium and the West, passed into the hands of the Venetians and Ottomans twice, and was the first Ottoman held castle to be captured by the Greek revolutionaries in 1821. Monemvasia has been celebrated by poets and artists, especially by Yannis Ritsos, who was born there and became one of the greatest contemporary Greek poets (repeatedly nominated for a Nobel Prize for Literature and received the Lenin Peace Prize). For nearly a century, Monemvasia has been protected by the Greek state because of its historical and environmental importance. After a phase of population decline in the post-war years, Monemvasia has been revived since the 1970s with the reconstruction of the Lower Town, a feat stimulated through international interest in the unique natural beauty and monuments of the site.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

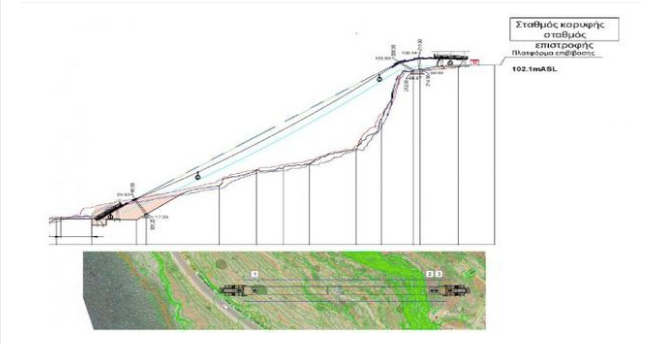

The Greek government is currently planning to build a cable car which will connect the area in front of the gate of the Lower Town with the Upper Town of Monemvasia. From ancient times until today, the connection between the two areas was made possible by a fortified uphill path that is 220 m long and requires a hike of only 9 minutes according to signage by the Ministry of Culture. The cable car project and associated landscaping would span an area of 310 acres! The total project, which is estimated to cost €6,800,360, will be funded by the European Recovery and Resilience Plan, and will include:

- The installation of a cable car with gondolas at a distance of only 150 m. from the main gate of the Lower Town, in order to facilitate access from the level of the asphalt road which leads from this area to the Upper Town (the difference in elevation being 90 m.);

- extensive digging out of rock in an archaeological area, lying only 150m. from the main gate of the Lower Town;

- the construction of two passenger service stations (one at the level of the Lower Town and one in the Upper Town) with a large surface area and a height corresponding to a four-storey building;

- the construction of three support pillars of the same height as the two stations;

- the construction of a long concrete ramp (in the form of an inverted N-shaped bridge) adjacent to the Upper Town passenger service station; and

- extensive landscaping extending from the Upper Town passenger service station to the best-preserved monuments of the Upper Town.

This project, as described in the minutes of the relevant meetings of the Central Archaeological Council and in the Environmental Impact Study prepared by regional/municipal authorities, raises numerous questions and does not provide many clear answers:

1) Is it a cable car or a lift and which one is preferable?

The official documents of the Ministry of Culture and the Regional Government/Municipality name the project as a "lift", but they describe and sometimes they clearly show that a cable car is planned. A cable car and a lift are different means of transport. One must question why is double-speak being used by the authorities? Also, why have they not released the scientific and other data on the basis of which the cable car solution was preferred over the lift solution?

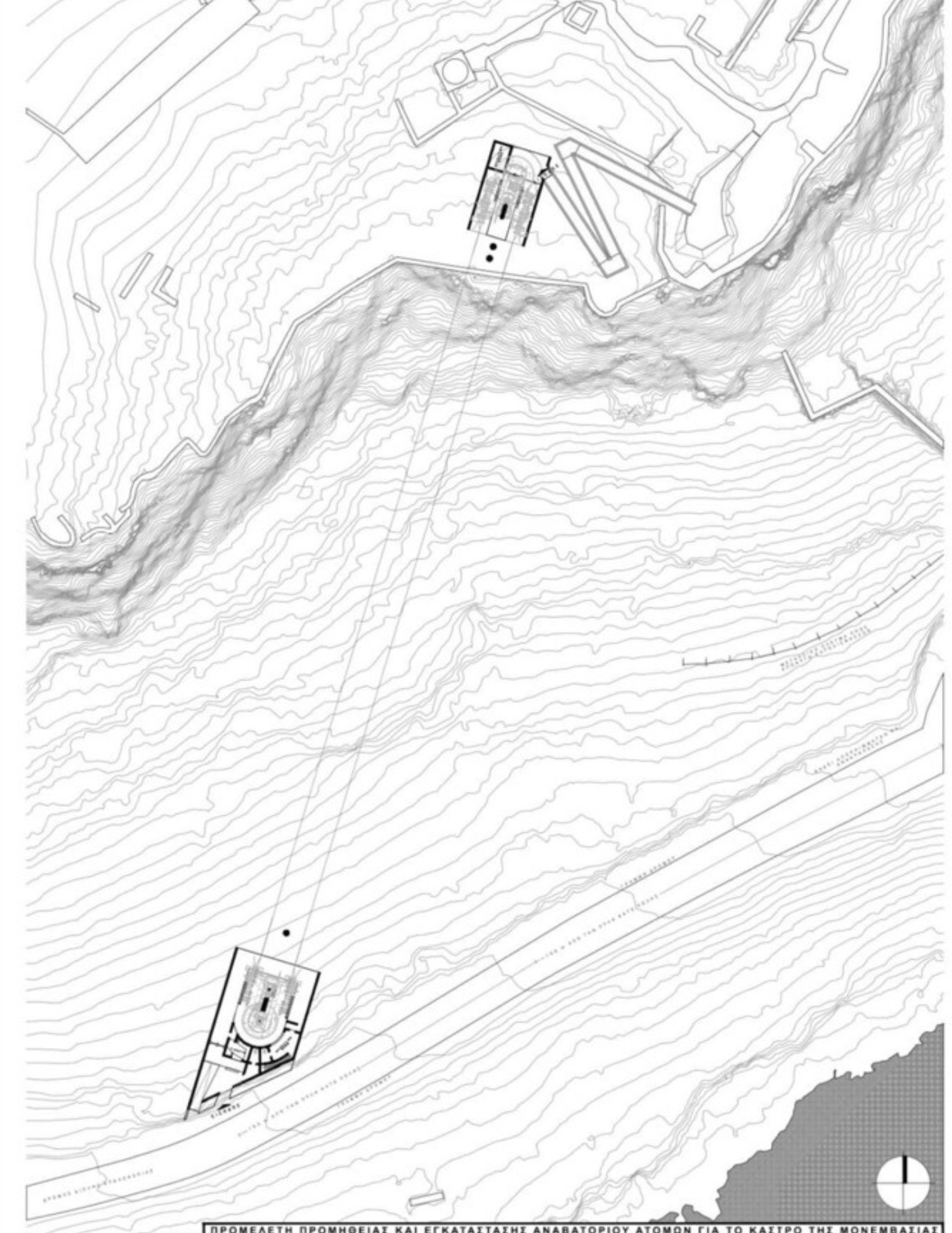

Monemvasia: Plan of the cable car route, the passenger service stations and the ramp adjacent to the Upper Town station.

It should be noted that an outdoor lift connecting the Lower Town and Upper Town was established roughly a decade ago and operated for a few years near the main gate of the Lower Town to serve the needs of archaeological restoration work on the Upper Town. That work did not cause any controversy, unlike the present project. The contrast begs the question: Why not invest the European funds in the tested and uncontroversial solution of the lift, which will serve passengers, but also have a reversible form and a scale which has no major negative footprint on the environment and the monuments?

2) Who opposes the construction of the cable car?

The cable car project was not subjected to any process of public consultation, which deprived people and institutions with extensive experience in general cultural and environmental issues from the opportunity to provide constructive feedback. Apart from The Association of the Friends of Monemvasia, which has appealed to the Greek Council of State and has organised a public conversation on the issue, many bodies with decades of experience in the protection of the environment and culture have also expressed their opposition:

The Greek section of the International Council on Monuments and Sites The Association of Greek Archaeologists The Society for the Environment and Cultural Heritage The Monumenta organisation The Hellenic Society for the Protection of Nature Callisto: Environmental Organisation for Wildlife and Nature Medasset: Mediterranean Association to Save the Sea Turtles The Ecological Recycling Society The Organisation Earth The Society of Cultural Heritage Management Consultants (ESDIAPOK)

In addition, a number of academics from related disciplines (archaeologists and architects) have published deep concerns about the project, while a significant component of the local community (irrespective of their political affiliation) is also deeply concerned. The last point is highlighted because it is occasionally reported falsely by representatives of the municipality and the government that there is widespread local support for the project. However, at both the municipal and regional level, the largest minority parties did not vote in favour of the project. Therefore, the claim of widespread local support is unfounded.

3) Why do many people and institutions oppose the construction of the cable car?

Numerous people and institutions oppose the plan for the construction of the cable car for five main reasons, which are listed herein and are explained below:

Α) the project promotes environmental degradation and damage to cultural heritage;

B) it has stated purposes which blend pretexts and contradictory reasoning;

C) it comes in both form and scale which do not fit the natural and cultural landscape of Monemvasia;

D) it does not rely on expert studies produced by state agencies and independent experts, but assigns such studies to the private contractor commissioned to execute the project; and

E) it is not accompanied by a financial viability assessment.

Let us have a closer look at each individual point:

A) The project promotes environmental degradation and cultural heritage damage

For many decades the Greek state has protected Monemvasia with strict policies and regulations which ensured the revival and sustainable development of the site. The state has designated the Castle of Monemvasia as a historical and archaeological site, a protected area in the NATURA 2000 protected areas network and an old-growth forest area. These resolutions imposed increased protection for the environment and cultural heritage of the site and restrictions on construction and other development.

The project of the cable car marks a remarkable shift on the part of the Greek Ministry of Culture from the policies of limited development and ambient lighting in the night, which it has long established and honoured. Indeed, the cable car project will be the largest development project on the rock in over two centuries and probably the largest ever conducted after the construction of the fortification walls. Partly made of concrete, and partly of metal and moving parts, the cable car will be contrary to the aesthetics and the history of Monemvasia and will degrade the visitor's experience of the defensive character of the site, which is the most essential condition for which the place was settled to begin with. Additionally, the project will produce a fait accompli, before the completion of the Management Plan for the Castle of Monemvasia, which the Ministry of Culture itself has commissioned from an independent team of experts. One must therefore pose the question: why the rush?

Comparable plans for building cable cars at major archaeological sites around the globe which attract hundreds of thousands of visitors have provoked serious reactions from the international community and from leading cultural institutions. For example: UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) intervened to stop cable car projects at Mount Sinai in Egypt, Machu Picchu in Peru, and le Krak des Chevaliers in Syria, and it regulated for the dismantling of the temporary cable car that was put up in the Rhine Valley in Germany. Likewise, the plan for building a cable car over the Castle of Belgrade led Europa Nostra (the leading organisation for the protection of cultural heritage in Europe) to include the monument among Europe's seven most endangered sites in 2020 and to observe that the work would drastically compromise the authenticity and integrity of the site.

In the light of these international developments, the cable car project of Monemvasia is likely to generate negative publicity for the site in the international press and to attract criticism by international organisations. Furthermore, the project would undermine any future effort to nominate the Castle of Monemvasia as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a distinction which brings enormous international visibility and both cultural and financial benefits.

B) The project has stated purposes which blend pretexts and contradictory reasoning

The Ministry of Culture declares that the project is part of its policy to promote universal accessibility of archaeological sites for disabled people; however, the regional/municipal authorities have different agendas concerning the project and they emphasise how it will generate revenue. More specifically:

The Ministry of Culture's emphasis on universal accessibility and their implementation of related projects in many cultural venues is commendable. However, the argument for universal accessibility seems spurious in the case of Monemvasia since:

• no other accessibility project of such a large scale has been carried out elsewhere in Greece. The selection of Monemvasia as a priority for the implementation of the project results from neither the expressed priorities of associations representing people with disabilities nor from the scale of tourist flows to Monemvasia in general and its Upper Town in particular. Why is such a project not carried out, for example, at the sanctuary of Delphi, a UNESCO World Heritage Site which attracts many more thousands of visitors and is located on a steep slope which is difficult to climb?

• in the Lower Town of Monemvasia, which is the main attraction for visitors to the area and the most important tourist destination in southern Laconia, no work has been carried out and no work is currently planned to ensure universal accessibility. This is despite the fact that the Lower Town has many stepped pathways and steep slopes which prevent people with mobility issues from accessing even the most important local monuments (e.g. the Church of Elkomenos Christos) and museums (e.g. the Monemvasia Archaeological Collection) which are managed by the Ministry of Culture; and

• if the reference to universal accessibility was not spurious, the state authorities would not leave it to the contractor to decide whether to build steps or ramps for the project (which obviously makes a big difference for people with mobility issues). Likewise, if the reference to universal accessibility was not spurious, the Environmental Impact Assessment would not have overlooked the issue of how disabled persons would even approach the cable car, given major problems of traffic and parking in front the main gate to the Lower Town.

In contrast to the Ministry of Culture, the regional/municipal authorities advertise the project as a revenue generating mechanism. More specifically, in the Environmental Impact Assessment which they produced and approved, the regional/municipal authorities explain the purpose of the project as follows:

• it will serve the permanent residents of the Upper Town of Monemvasia (note that the Upper Town has been entirely abandoned for more than two centuries and is utterly uninhabited; even the Lower Town is thinly populated for most of the year, with only 11 permanent residents according to the 2011 census);

• it will serve to promote visiting the Upper Town;

• it will facilitate the work of the archaeological service; and

•it will serve people with mobility issues.

In the same study, the list of project benefits does not include any reference to people with disabilities. Indeed, the following benefits are identified:

(a)easier access for residents and visitors;

(b)boosting revenue;

(c)creation of jobs; and

(d)safe transport.

This order of priority excludes the accessibility by disabled people, which is only noted as a collateral benefit.

Why do the Ministry of Culture and the regional/municipal authorities have different and partly conflicting agendas for the project? The conflict emerges from the repeated references to the possibility of introducing ticketing, which are made by the regional/municipal authorities in the Environmental Impact Assessment. How can this revenue-raising approach be reconciled with the stated intention of eliminating discrimination against people with disabilities?

C)The project comes in a form and scale which do not fit the natural and cultural landscape of Monemvasia

The idea of building a cable car leading to the Upper Town of Monemvasia dates back to 1965, when the Greek National Tourism Organisation also planned to build a hotel in the ruined Upper Town! This project was quickly abandoned, but it has now been resurrected after more than half a century of oblivion. This is despite the fact that, internationally, approaches to the management and protection of sites of archaeological and environmental interest have changed radically over the last half century and current approaches generally favour contained and reversible interventions.

The proposed cable car project of Monemvasia extends over a vast area of 310 (!) acres, and includes:

• the construction of two large passenger service stations. The most restrictive proposal prescribes that the Lower Town station will be built only 150m from the main gate of the Lower Town, in the form of a building of 230m2, 12.5m in height, i.e. equal to a four- storey building and probably taller than any other building on the rock (and probably one of the tallest in the entire region of Laconia). In order to make the 'four-storey building' less conspicuous, the project involves the extensive digging out of the rock – a rock which has been celebrated by poets and travelers from around the globe and is designated as a protected site of archaeological and environmental interest. The Upper Town station will be smaller, but of unclear height;

• the construction of three support pylons along the route of the cable car; and

• the construction of a long concrete ramp (in the form of an inverted N) adjacent to the Upper Town passenger service station.

The stations, the pylons and the ramp – which are all irreversible structures – will be made of concrete, even though the Greek state regulates that buildings on the rock of Monemvasia should involve local stone and have no exposed concrete surfaces. The structures made of concrete, the wire ropes and the metal gondolas are in every sense contrary to the aesthetics and history of the site. A representative of the municipality has reassured the community that the Central Archaeological Council sees no degradation caused by the project. However, this is clearly not the case. The minutes of the proceedings of the relevant meeting of the Central Archaeological Council and the Environmental Impact Assessment repeatedly state that theproject gives the "impression of a seemingly mild intervention", which basically reaffirms that it is not a mild intervention (it only looks like one, in the eyes of those promoting the project). Moreover, the minutes of the proceedings of the Central Archaeological Council refer to the problems “caused by the construction of an entirely modern building in close proximity to the entrance gate and the fortification wall”, while an expert who participated in that meeting noted that the cable car “will be the dominant feature in Monemvasia”. Indeed, the cable car will be visible in every panoramic photograph of the Castle and will pose problems to the production of films and related works which have often chosen Monemvasia because of its unspoiled aesthetics.

D)The project does not rely on expert studies by state agencies and independent experts, but assigns such studies to the private contractor commissioned with the work

The expert study needed for the design and financing of the project will not be conducted beforehand by state agencies and independent experts. Instead, the project budget was conceived independently of any such studies and on the basis of this unsound footing the work was awarded to a private contractor who was also commissioned with carrying out the expert studies (which themselves should have been done by third-party experts), defining essential parameters of the project and evaluating its impact on the landscape and monuments, with state agencies being limited to a monitoring role.

This planning raises serious questions; in particular, why have the relevant state agencies not produced their own studies and/or assigned such studies to independent experts to:

•introduce safety provisions and develop accurate budgeting before they assigned the project to a contractor? The Municipality of Monemvasia is aware of a report by a team from the Polytechnic University of Athens (dated 14 June 2020) that has emphasised that the area where the cable car is now being planned presents serious risks of rockfall, a risk which is also recognised by the Central Archaeological Council. Why did the regional/municipal authorities take no action on this matter before the project was awarded to a contractor, especially given that they conducted comparable work on the part of the rock overhanging the Lower Town? Why is there no expert study to evaluate the impact of the exceptionally strong winds which blow in the area on the operation of the cable car or on the impact that the project will have on the traffic along the narrow road that leads to the main gate of the Lower Town, which has often proven dangerous for both car drivers and pedestrians?

•evaluate the environmental degradation that will be caused by the project? Why have they not consulted with the Agency for the Natural Environment and Climate Change on the project, since this is the institution which advises on any development in a Natura 2000 network area?

•evaluate whether the construction of the cable car is safe for the monuments? This applies especially to the section of the fortification walls which are located next to the arrival point of the cable car in the Upper Town and next to the major pillars which will carry heavy freight. Will the excavation for the foundation of these modern structures not affect the fortification walls which lie a few meters away? It should be noted that the simple risks of rockfall arising from gravity and seismic activity have led the authorities to engulf the section of the fortification walls of the Upper Town which runs above the Lower Town in metal wire mesh. There are therefore serious considerations relating to health and safety that are currently being ignored!

E)The project is not accompanied by any financial viability assessment

The regional/municipal authorities declare that the revenue generated from the cable car will contribute to touristic development, but they have not provided any financial or other data on this idea. The argument overlooks the fact that:

•there can be no greater attraction than the rock and the Castle themselves. There is no data to show that tourists choose vacation destinations based on the existence of cable cars. The cable car may reduce rather than increase quality tourism, which promotes sustainable development and is more profitable and less damaging to Monemvasia than the mass tourism of cruise ships which has been favoured over the last couple of years;

•in the few cases where experts have polled visitors over their experience of an archaeological site supported by a cable car (e.g. in Wulingyuan, China), they have identified widespread complaints that tour operators are shortening the time allocated to the visit due to the existence of this means of transport. The same experts identified extensive complaints about long lines and delays for using the cable car and, in any case, they found that the visitors did not consider the cable car as an important feature of their positive experience of the site. These considerations suggest that a cable car can negatively impact the attraction of a site to visitors and the economic benefits to the local community;

•this cable car project has a budget for maintenance and repair which extends over the first two years and is slightly over €100,000. How will future maintenance costs be covered? Will they be paid by the local community in the guise of municipal taxes? Or will they be paid by the disabled people using the cable car through a discriminatory policy on ticketing?

•there is no study on the cost of operation of the cable car, especially concerning staff salaries. For the universal accessibility premise to work, the use of the cable car must extend over normal working hours throughout the year. Has this cost, which falls on the As in the case of maintenance costs, will this be paid by the local community or by disabled people using the cable car?

•in the unfortunate case of a serious accident (like those attested for other cable cars around the world), which institution will bear the heavy cost of damages and with what funds?

In the light of these concerns, the Association of the Friends of Monemvasia proposes:

•The cancellation of the plan for the installation of a cable car and its replacement by a plan for a lift, which is a solution that has been successfully tested at the site and will serve disabled people without causing any major degradation on the environment and the monuments of this unique site, which is Monemvasia.

•The implementation of measures that will increase both safety and accessibility in the Lower Town (which attracts most visitors who come to Monemvasia) and along the historic path which runs from the Lower Town to the Upper Town.

•The planning of the relevant projects should comply with: (a) both Greek and European legislation; (b) best international practices regarding the protection of cultural heritage and the environment in designated archaeological sites which fall within Natura 2000 protected areas; and (c) the Management Plan for the Castle of Monemvasia which is currently being prepared by an interdisciplinary team of experts.